Déjà vu - that sudden, inexplicable feeling that the exact event you are experiencing has happened to you before, in exactly the same way, even though the logical part of your brain knows that it can’t have. Most of us have experienced it at some time or another, but very little is known about what actually causes it. The name comes from the French for ‘already seen’, although this name does not explain the phenomenon fully - as well as feeling you have already seen something, for déjà vu to occur, you must also know that you have not.

|

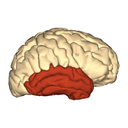

| The Temporal Lobe is the part of your brain just above your ears. Image credit: wikimedia commons |

Although for most of us this feeling is harmless, if rather disconcerting at times, for some people it can be a warning sign for something more sinister. Déjà vu experiences have been linked with temporal lobe seizures in epilepsy sufferers. Partial seizures affect only a small area of the brain, so cause different symptoms depending on where they occur. Generally the patient remains conscious and may not even realise that they are having a seizure. The temporal lobes are located above the ears, and contain areas of the brain responsible for memory, as well as language production and comprehension, emotion, and some higher level visual and auditory processing, such as face recognition. These broad ranging functions mean that seizures to this area can cause a variety of unusual symptoms, such as experiencing sensations without a cause, rushes of emotion, or memory problems, including déjà vu. Temporal lobe seizures have even been linked with religious experiences.

|

| Deja vu isn't the only thing that happens when we're tired which we don't understand - why do we yawn? Photo: Eli Duke |

One of the major barriers for research into déjà vu is the inability to provoke it, or even to predict when it might happen. For this reason the majority of research has been based on questionnaires about people’s past experiences. While these can provide interesting information on the frequency and subjective elements of déjà vu, they do not help elucidate its brain basis. These kinds of studies, however, have thrown up some interesting points. Déjà vu is more common in people from higher economic classes, and those who are more educated. It is more common in younger people, with the frequency decreasing dramatically with age. People who travel more frequently report higher instances of déjà vu, although this may be explained away by the fact that they will encounter more novel environments, which are vital for the feeling of déjà vu. The experience also seems to be more likely when fatigued or stressed, which may have some implications for its cause.

Despite the difficulties in conducting experiments around déjà vu, several hypotheses have been put forward to explain the phenomenon:

Memory

|

| Though a scene is new, elements of it may be familiar Photo by Ngsyatowuahg [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons |

When we recall a memory, there are two aspects to it - we get a feeling of familiarity, of recognising something or someone, and we also have the memory of where we know them from. This second aspect is known as source monitoring, and some people find it easier than others. One hypothesis is that déjà vu may occur when the feeling of familiarity is there, but your source monitoring has failed. However déjà vu only occurs in novel places, which you know you have never been to before. So how can there be a feeling of familiarity? Proponents of this theory suggest that that you could have seen of the scene before, but be unable to place them because they are in a different context. You may even have seen the scene on television, but if you are unable to place the feeling of familiarity, the conflict between this feeling and your knowledge that you haven’t been to this place before could produce the feeling of déjà vu.

Recent research at Colorado State University supports this theory. Researchers there have used virtual reality to immerse participants in various scenes. They found that déjà vu is provoked more regularly when the layout of a scene is similar to one that has been seen previously, even when the details are different. If this earlier scene is not consciously recalled, the similarity is enough to provoke a feeling of familiarity, which along with the knowledge that the scene is new, produces the feeling of déjà vu.

Another possibility is that although the setting isn’t actually familiar, the processes your brain undergoes when seeing it may be. It is well documented that recall is easier when the situation is similar to that in which you learn the information. It may therefore follow that similar brain processes could lead to an artificial feeling of familiarity.

Neurological

It's also possible that a brief dysfunction of the nervous system in the right hemisphere could be the culprit. This could be a small seizure, fatigue or some other effect that causes a delay in transmission. This delay could then be misinterpreted as meaning the information is old. This idea, however, does not fit with experimental findings which suggest that previously encountered information is usually processed more quickly, so if information was processed slowly, this would be more likely to suggest it is new.

Another idea is that there may be two pathways involved in processing stimuli. If one of these was delayed for some neurological reason, the information would appear to be familiar when it reached the brain via the second pathway, as it had already arrived via the first.

Attention

|

| A shop window, glanced at unconsciously, may later seem familiar when looked at properly. Image credit: wikimedia commons |

Déjà vu is a poorly understood phenomenon, especially considering how common it is. Although many theories have been suggested, it is very difficult to devise experiments to test them, leading the majority of scientists to abandon it as a research area. If we could find a way to reliably induce the feeling, this would allow imaging studies to determine which areas of the brain are involved and this, along with other experiments, could give us a better idea of why and how déjà vu occurs. Until this breakthrough happens, however, déjà vu is likely to remain another Thing We Don’t Know.

No comments:

Post a Comment