|

| Narwhal illustration. Strangely, there are few good pictures of these animals as they spend most of their time partially submerged. PublicDomainPictures.net |

Search our site

Friday, 18 February 2022

Why do Narwhals have tusks?

Friday, 4 February 2022

Green ammonia

Ammonia may be a chemical you don't think about very much – but, perhaps, you should...

75-90% of all the ammonia made is used to make fertiliser, which is used to grow 50% of global food. Other industries that use it include pharmaceuticals, plastics, textiles, and explosives. We call it a “nexus molecule”.

But it's more than just that. Ammonia might be used in the future as a chemical energy store, costing energy to make and releasing it when its burnt. Better than other materials such as hydrogen, it's nowhere near as flammable nor as expensive to keep liquid, requiring achievable pressures of 10-15 bar or -33°C.

It also has the potential to put a massive dent in our greenhouse gas emissions and could be critical to achieving net zero carbon by 2050 – the current global target. This is because of one of its main ingredients, hydrogen: made by steam reforming the fossil fuel methane, it contributes ~1.8% of global carbon dioxide emissions. We could replace this with blue hydrogen, using carbon capture and storage of all CO2 emissions to achieve net zero carbon, or better – green hydrogen, generated from water via electrolysis and 100% renewable energy resources.

We can also massively improve the synthesis of ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen, using lower pressures and temperatures, or exploring fascinating biochemical or electrochemical methods, where scientists employ bacterial enzymes or metal catalysts (perhaps nanocatalysts) to make it from nitrogen. These processes are still in the works, but have the potential to entirely reform the way we see green chemistry.

Bring on the ammonia revolution!To find out more about green ammonia, check out our new article on the topic.

Thursday, 13 January 2022

The cannibal in the ocean

|

| Orthacanthus. SaberrexStrongheart via chondrichthyes.fandom.com/wiki. |

Tuesday, 14 December 2021

Wielding (quantum) fields!

|

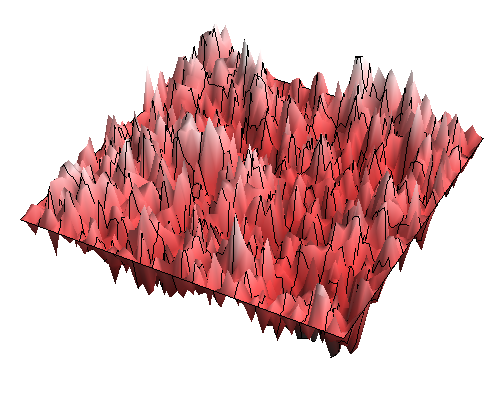

| Gaussian free field model by Samuelswatson via Wikipedia. |

Friday, 3 December 2021

What has Juno found on Jupiter? Part II – It’s magnetic

|

| Jupiter's magnetosphere showing the Io Plasma Torus (in red). Yned via Wikipedia Commons. |

Wednesday, 17 November 2021

What has Juno found on Jupiter? Part I – Water and weather

|

| The Great Red Spot has been observed for over 300 years now. It's so large it could accommodate three Earth-sized planets! Wikimedia Commons |

Sunday, 7 November 2021

Moving moss

Known as “glacier mice”, these moss balls are understudied, but recently researchers have taken notice of them and their weird, herd-like behaviour[1]. This has led to all sorts of questions and a couple of published papers on the phenomenon, such as...

How do they form?

Researchers have theorised that the moss balls form through “nucleation” at rough points on the glacier surface – just as crystals start growing on impurities in their containers. First, one crystal or drifting moss fragment attaches, and then others attach onto that, gradually coming together to make the shape of the final structure. It’s not clear how this always leads to oval balls, and none of them are round, but it does generally make sense as a theory.Wednesday, 27 October 2021

Transphytoism

New tech has ripped bits out of a venus fly trap and integrated them into a new robot to mechanise a grabbing claw. It is, if you like, a Frankenstein’s monster of the plant world, a terminator to terrorise all triffids. Or, you know, a cool little gadget. A bit like a litter-picker.